Program Description

The Mozambique Channel is a known biodiversity hotspot for cetaceans, with at least 22 species documented. This includes several Endangered or Critically Endangered species or subspecies of baleen whales, most of which are migratory and have poorly understood movement patterns and seasonal distributions. Passive Acoustic Monitoring (PAM) is a widely used and effective technique for detecting the presence of cetaceans, and involves listening for known vocalizations with underwater microphones, or hydrophones, often continuously for long periods of time with autonomous remote recorders. Not long as we entered the 2000’s, conducting long-term PAM could only be done with large budgets using expensive and cumbersome equipment that required challenging logistical hurdles, such as large oceanographic vessel ship time. Recent technological advances have resulted in commercially available autonomous recorders that are highly compact (the size of a soda can), relatively inexpensive, and highly effective (able to record continuously for many months without servicing). The use of such recording devices is rapidly revolutionizing what is known about cetaceans, particularly in remote difficult-to-work-in regions, where little funding is available, like the coasts of Africa.

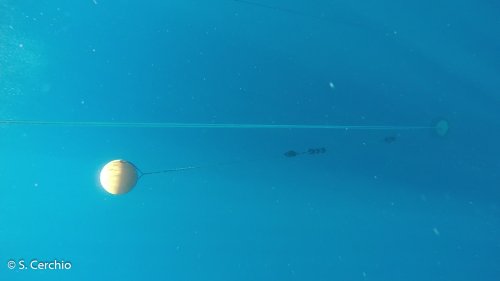

Dr. Salvatore Cerchio has been conducting a PAM study off the west coast of Madagascar since 2016, with remote recorders operating constantly for each year since the start of the study. The work started in the northwest off the island of Nosy Be, as part of the Omura’s whale project, monitoring in the shallow continental shelf waters with bottom mounted recorders placed at 40m depths that were serviced by SCUBA diving. The main focus was to define the spatiotemporal distribution of the species over the course of a year in the study region of the project. In 2017, this work expanded to the monitoring of deep waters on the shelf slope, placing several recorders at 300m by using deep water “acoustic releases” that allow the retrieval of remote recorders using an acoustic trigger mechanism from a small boat at the surface. This work was focused primarily on blue whales and other migratory baleen whales. Currently, the project is monitoring at three different locations along a 1400km stretch of the west coast of Madagascar, including: Nosy Be in the northwest, continuing the monitoring started in 2016; Mahajanga on the central coast, started in late 2019; and Toliara in the southwest, started in 2018. Several important and surprising discoveries have been made, and the work and analysis of existing data is only getting underway.

Here is a list of the some of the whales that have been detected and what we have learned so far:

- Omura’s whales (Balaenoptera omurai) – with so little known about this species, the first important discovery was the fact that they are very vocal and produce a stereotyped repetitive song, like other rorqual baleen whales. Individuals can sing for many hours uninterrupted (12 hours continuous is the longest recorded to date) and sometimes they sing in a chorus of many individuals. Long term PAM indicated that the population is non-migratory, sings year-round, strongly prefers shallow shelf habitat to deep water continental slope habitat, and some areas within their habitat are much more preferred for singing than others.

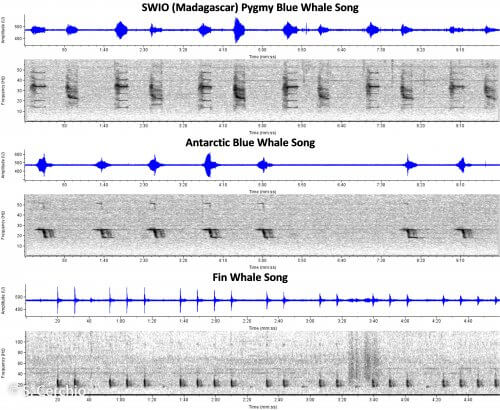

- Southwest Indian Ocean (SWIO) population of pygmy blue whale – (Balaenoptera musculus brevicauda) – Blue whales in the Indian Ocean and divided into 2 or 3 different subspecies, and the distribution and movement patterns of the pygmy blue whale subspecies is poorly understood. SWIO pygmy blue song was the most common among all blue whale populations detected and was present twice during the year in May-July and October-January. This pattern suggests a previously unrecognized migratory corridor between summer feeding and winter breeding grounds south and north of Madagascar, respectively.

- Antarctic blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus intermedia) – This subspecies of blue whale was hunted extensively in the 20th century in Antarctica and the Southern Ocean and remains Critically Endangered. Spending the Austral summer feeding along the Antarctic ice edge, their winter distribution and breeding areas are poorly understood. Antarctic blue song was present in the northern Mozambique Channel throughout the Austral winter from June to September (overlapping with the first peak of SWIO pygmy blues), suggesting a previously unrecognized breeding season aggregation.

- Northern Indian Ocean pygmy blue whales – “Sri Lanka” blue whale song, and “Oman” blue whale song were detected for short periods between January and May. Individuals from these populations appear to be occasional visitors to the Mozambique Channel.

- Fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus) – Southern hemisphere fin whales are known from the Southern Ocean, but their winter ranges are poorly defined. Fin whale song was present during the late Austral winter, from early August to mid-September, suggesting winter breeding habitat but a later arrival than Antarctic blue whales and a lower rate of occurrence and occupancy, potentially representing the northern extent of breeding range.

- Antarctic minke whale (Balaenoptera bonaerensis) – The pulse trains widely recorded around the Southern Ocean and often referred to as “the bioduck” were only recently associated with Antarctic minke whales. We recorded three distinct song types from the species, found to be very common in the higher bandwidth. Antarctic minke whales were present during the Austral winter/spring from at least early July to early November, so remaining seasonally later than Antarctic blue or fin whales.

- Dwarf minke whale (Balaenoptera acutorostrata) – This minke whale is a subspecies of the Northern Hemisphere common minke whale, and found throughout the Southern Ocean, however like most migratory species their distribution is poorly studied. Dwarf minke whale vocalizations were heard sporadically in the shallow waters north of Nosy Be when monitoring for Omura’s whales and appear to share this habitat but may be rare.

- Humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) – In addition to documenting the lesser known species of rorquals above, the monitoring has also detected the expected seasonal presence of humpback whales, whose use of Madagascar as winter breeding habitat is well documented. Recordings made during this project will be used in a regional study of migratory timing and song structure variation in the Southwest Indian Ocean, led by the Reunion NGO Globice.